Lessons Learned: Bad Data and other SNAFUs

Posted on Mon 15 February 2016 in TDDA

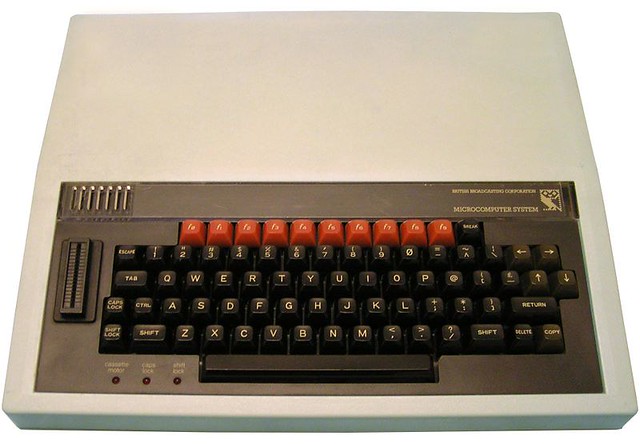

My first paid programming job was working for my local education authority during the summer. The Advisory Unit for Computer-Based Education (AUCBE), run by a fantastic visionary and literal "greybeard" called Bill Tagg, produced software for schools in Hertfordshire and environs, and one of their products was a simple database called Quest. At this time (the early 1980s), two computers dominated UK schools—the Research Machines 380Z, a Zilog Z-80-based machine running CP/M, and the fantastic, new BBC Micro, 6502-based machine produced by Acorn, to specification agreed with the British Broadcasting Corporation. I was familiar with both, as my school had a solitary 380Z, and I had harangued my parents into getting me a BBC Model B,1 which was the joy of my life.

The Quest database existed in two data-compatible forms. Peter Andrews had written a machine code implementation for the 380Z, and Bill Tagg himself had written an implementation in BBC Basic for the BBC Micro. They shared an interface and a manual, and my job was to produce a 6502 version that would also share that manual. Every deviation from the documented and actual behaviour of the BBC Basic implementation had to be personally signed off by Bill Tagg.

Writing Quest was a fantastic project for me, and the most highly constrained I have ever done: every aspect of it was pinned down by a combination of manuals, existing data files, specified interfaces, existing users and reference implementations. Peter Andrews was very generous in writing out, in fountain pen, on four A4 pages, a suggested implementation plan, which I followed scrupulously. That plan probably made the difference between my successfully completing the project and flailing endlessly, and the project was a success.

I learned an enormous amount writing Quest, but the path to success was not devoid of bumps in the road.

Once I had implemented enough of Quest for it to be worth testing, I took to delivering versions to Bill periodically. This was the early 1980s, so he didn't get them by pulling from Github, nor even by FTP or email; rather, I handed him floppy disks,2 in the early days, and later on, EPROMs—Erasable, Programmable Read-Only Memory chips that he could plug into the Zero-Insertion Force ("ZIF") socket3 on the side of his machine. (Did I mention how cool the BBC Micro was?)

Towards the end of my development of the 6502 implementation of Quest, I proudly handed over a version to Bill, and was slightly disappointed when he complained that it didn't work with one of his database files. In fact, his database file caused it to hang. He gave me a copy of his data and I set about finding the problem. It goes without saying that a bug that caused the software to hang was pretty bad, so it was clearly important to find it.

It was hard to track down. As I recall, it took me the best part of two

solid days to find the problem. When I eventually did find it, it turned

out to be a "bad data" problem. If I remember correctly, Quest saved

data as flat files using the pipe character "|" to separate fields.

The dataset Bill had given me had an extra pipe separator on one line,

and was therefore not compliant with the data format. My reaction to

this discovery was to curse Bill for sending me on a 2-day wild goose

chase, and the following day I marched into AUCBE and told him—with

the righteousness that only an arrogant teenager can muster—that it

was his data that was at fault, not my beautiful code.

. . . to which Bill, of course, countered:

"And why didn't your beautiful code detect the bad data and report it, rather than hanging?"

Oops.

Introducing SNAFU of the Week

Needless to say, Bill was right. Even if my software was perfect and would never write invalid data (which might not have been the case), and even if data could never become corrupt through disk errors (which was demonstrably not the case), that didn't mean it would never encounter bad data. So the software had to deal with invalid inputs rather better than going into an infinite loop (which is exactly what it did—nothing a hard reset wouldn't cure!)

And so it is with data analysis.

Obviously, there is such a thing as good data—perfectly formatted, every value present and correct; it's just that it is almost never safe to assume that data your software will receive will be good. Rather, we almost always need to perform checks to validate it, and to give various levels of warnings when things are not as they should be. Hanging or crashing on bad data is obviously bad, but in some ways, it is less bad than reading it without generating a warning or error. The hierarchy of evils for analytical software runs something like this:

-

(Worst) Producing plausible but materially incorrect results from good inputs.

-

Producing implausible, materially incorrect results from good inputs (generally less bad, because these are much less likely to go unnoticed, though obviously they can be even more serious if they do).

-

(Least serious) Hanging or crashing (embarrassing and inconvenient, but not actively misleading).

In this spirit, we are going to introduce "SNAFU of the Week", which will be a (not-necessarily weekly) series of examples of kinds of things that can go wrong with data (especially data feeds), analysis, and analytical software, together with a discussion of whether and how it was, or could have been detected and what lessons we might learn from them.

-

BBC Micro Image: Dave Briggs, https://www.flickr.com/photos/theclosedcircle/3349126651/ under CC-BY-2.0. ↩

-

Floppy disks were like 3D-printed versions of the save icon still used in much software, and in some cases could store over half a megabyte of data. Of course, the 6502 was a 16-bit processor, that could address a maximum of 64K of RAM. In the case of the BBC micro, a single program could occupy at most 16K, so a massive floppy disk could store many versions of Quest together with enormous database files. ↩

-

Zero-Insertion Force Socket: Windell Oskay, https://www.flickr.com/photos/oskay/2226425940 under CC-BY-2.0. ↩